I hadn’t expected to be drawn to reread David Satter’s It Was a Long Time Ago and it Never Happened Anyway examining the horrors of the Stalin era and the aftermath which continues to this day. However, current affairs and the state of the world made its siren call irresistible.

It’s not that the book is a bad one, quite the contrary. It’s excellent, enthralling, appalling, sickening, frightening. At least, it was 10 years ago when it came out. Now, under the harsh spotlight of the last few years, it’s all that and more; frankly, it’s terrifying.

What a complacent fool I was when I read it for the first time. I sat in my armchair and tut-tutted my way through, shaking my head, wondering how on earth such monstrous crimes and summary executions could ever have eventuated as they did. Nothing like that would ever happen in my lifetime, let alone to me. There would be signs along the way, wouldn’t there, where we could correct any dangerous societal tendencies? Surely!

Reading it now, the same awful patterns and reactions from that era are disturbingly recognisable in today’s society.

In the following extract, Lyubov Shaporina describes in her diary how she felt about the way executions were discussed:

The nausea rises to my throat when I hear how calmly people can say it: He was shot, someone else was shot, shot, shot. The word is always in the air, it resonates through the air. People pronounce words completely calmly, as though they were saying “He went to the theatre.” I think that the real meaning of the word does not reach our consciousness – all we hear is the sound. We don’t have a mental image of those people actually dying under the bullets….the words ‘shot’ and ‘arrested’ don’t make the slightest impact on young people.” The faces of ordinary people standing in long lines are “dull faced, embittered, haggard.” “It is unbearable,” she wrote, “to live in the middle of it all. It’s like walking around a slaughter house, with the air saturated with the smell of blood and carrion.” (emphasis added)

How calmly now we observe the spate of heart attacks, strokes and deadly collapses all around us, in young people, athletes, and middle-aged, too young to die. A stroke, we say, a heart attack. How calmly and readily we adopt a new acronym, SADS. How calmly we note the push to get defibrillators on every street corner. How calmly we say sudden stage four cancer, how calmly we say all cause mortality and excess deaths are rising, and fertility falling. And how calmly we listen to our executioners ‘experts’ as they tell us to take a third, fourth, fifth, shot, shot, shot. Talk about a slaughterhouse.

One page later, Satter writes:

In a gruesome way, the Great Terror primed Leningrad for the mass slaughter that was to come. During 1937-38, the city suffered at the hands of its own rulers. During the war it was besieged by a foreign enemy. But the murder of tens of thousands of selected individuals during the Terror prepared the people of the city to be sacrificed in the hundreds of thousands in the interests of the Soviet state. The principle had been established that the objectives of the state, justified or not, were the highest objectives of all. (emphasis added)

The whole world ‘suffered at the hands of its own rulers’ in the last few years. Melbourne certainly did. Perhaps not murder, but suffering for sure. It makes you wonder who, exactly, are our rulers? I dread to think what this experience has prepared us for. It sounds like an exam question 50 years from now : “The Great Terror is to WWII as the COVID era is to ???”

There’s no doubt that there is a collective memory and response now hard-wired into once-democratic societies, those like the people of Melbourne who bounced and lurched from lockdown to lockdown to lockdown to lockdown to lockdown to lockdown. The auto-response is to lie down like a lamb and take what’s coming. We’ve been exposed as cowards. God help us next time.

Satter interviewed Yuri Zhigalkin about his experience in his native town of Korsakov in the 1970s. Looking back at that time he describes a general way of living that just got on with the basics.

(Satter): “What the regime was telling its people and telling the world was cartoonish, but within that cartoon people were living a normal life?“

(Zhigalkin): “Exactly. That’s why some people miss that kind of life. At that time, their life was based on primitive things.”

It does feel to me like we are living within a cartoon. Donning masks that can’t possibly work, following arrows around stores, standing on the stickers, leaning around the perspex screens at the supermarket checkout. These are childish manifestations of megalomaniacal dictators’ and their apparatchiks’ whimsical deliberations: sit down to drink ok, stand up to drink not ok.

Only yesterday South Australia Chief Health Officer Nicola Spurrier (the same one who advised fans attending a football game to avoid touching the ball should it be kicked into the crowd, for fear of you-know-what) said during an interview ahead of the Christmas period “Father Christmas, you should have had your four doses of vaccine.” Here is the bureaucrat at the top of the health politburo literally talking out loud, on camera, to a figment of her imagination – and we’re supposed to take her seriously.

Does she hear voices as well? What are the voices saying to her? It’s beyond a joke now. But somehow, within that stupid cartoon, Melburnians and New Yorkers and Londoners alike managed to live their ‘normal’ life, somehow earning a living, caring for kids and elders, educating and celebrating, marrying and giving birth. Not everyone, of course. Not the suicides, not the ones who lost livelihoods, homes, marriages. But enough to give the impression that life carried on as normal. Will we ever shake off that cartoon and live in 4K Ultra HD again? I doubt it, not if our health officials keep experiencing these psychotic episodes.

Let’s assume for the moment, though it’s by no means guaranteed, that the COVID era will in fact become a time-bound relic of the past, as opposed to an embedded dystopia that lasts into the foreseeable future. Is it too soon to begin talking about ‘survivors’ of the COVID era? Who will they be? How will they talk about that time to younger generations, or to visitors from the few countries that didn’t fall into the trap? Satter writes:

In speaking about the Stalin period, the typical remark from survivors and ordinary citizens was the the years of mass killings were “terrible times,” a valid observation but one that implied that the terror was unavoidable, like the weather, and beyond any individual’s control. (emphasis added)

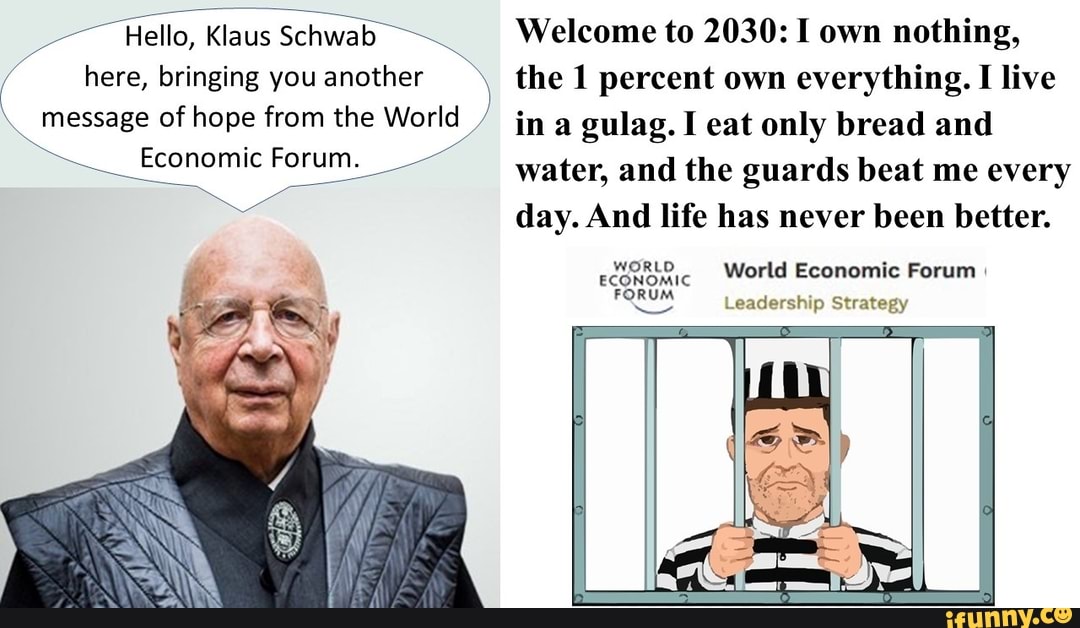

I already hear this kind of language: “Of course we couldn’t do that during lockdown” or “During COVID it was hard.” There is a reluctance to dwell on the horrors of the lockdowns and the vaccine mandates; better to get it all out of the way quickly with ‘“terrible time” and move on. Who will have the courage or the energy 20, 30, 50 years from now to tell it like it was? Will it even be possible? That depends entirely on whether we heed the lessons of Russia, or whether we let ourselves fall into the cold embrace of totalitarianism. We’re hearing the slogans already from the WEF: ‘You’ll own nothing and be happy.” Will we fall for it, or resist?

Satter again:

Besides security, Communism gave Russians a sense that their lives had meaning. The relation between man and God was replaced with the relation between man and the regime. The result was the elimination of a sense of universal values which depend on a supramundane source. But Russians received in exchange Marxism’s “class values” and a regime that treated itself as a single generator of absolute truth.(emphasis added)

Saint Jacinda has already told the inmates of Aotearoa (a.k.a. citizens of New Zealand) that she is their single source of truth. The West is well on the way to capitulation. The question is, what are we going to do about it?

I’m not sure that staying calm is the answer.