The Adelaide River Stakes is the name given to the mass exodus of people prior to and following the Japanese air-raid in Darwin on 19th February, 1942. Thanks mainly to an ill-informed statement by a former Governor General, Paul Hasluck, that it is a story full of shame for our national persona, but it is a myth.

The truth is that with much closer examination it was anything but a shameful episode in our most serious year of peril. The propaganda disseminated by the government of the day was based on inadequate information, over-the-top censorship and a failure to take the population into its confidence.

The faults lie with a succession of failed civilian and military administrations which, like the behaviour of most politicians, was a deliberate trail of cover-ups and refusal to admit fault.

In Darwin various plans were triggered in a somewhat state of mild panic. An evacuation plan had been drawn up by Edgar Harrison, Permanent OIC of Air Raid precautions. The plan, as a first priority, was to evacuate all women and children followed by other non-essential civilians. Darwin at the time had a population of 6,000. It had no sewerage system and relied on sea transport for its supplies of just about everything. There was no rail link and no paved road surface connecting south. Sea transport was the sole means of supply of bulk material. Air transport was virtually non-existent for these purposes. Preparations were made on the basis of the town being cut off from supply rather than being invaded.

When the Philippines fell a number of American ships made their way to Darwin thus increasing further the strains on the local economy and facilities. On 5th December Edgar Harrison handed the plan for evacuation to the Darwin Defence Coordination Committee comprised of the three service heads and the Administrator. The plan was accepted. Three days later Japan entered the war. Abbott did nothing to execute the evacuation plan.

On 11th December an air raid siren was accidentally set off resulting in a mild panic. The following day the four senior air raid wardens demanded that Abbott exercise his powers to declare a State of Emergency and commence the evacuation orders. Abbott refused stating that such a declaration would be bad for morale and cause panic. Curtin then stepped in and made the order to evacuate.

The purpose of this series is not to present a description of what happened before, during and after the 19th February, 1942. It is to refute the slur cast upon the Australian people by someone who would be expected to leap to our defence come what may. Perhaps Hasluck was the first of the woke brigade.

The myth created by Paul Hasluck was not that there was no evacuation but that it was a mad stampede which he described as a “day of national shame”.

Paul Hasluck had a distinguished but thoroughly useless career, first as an academic at the University of WA followed by a stint as a public servant then as an elected member of parliament where he served as a minister in the Menzies government. He was an unsuccessful contender for leadership of the Liberal Party and Prime Ministership claiming that he only nominated to prevent Billy McMahon being elected unopposed.

When John Gorton became PM he did not want a potential contender serving in his ranks so he promoted him to Governor General, a useless position for which Hasluck was well qualified with his public servant background and suffering from the bureaucratic disease of inertia.

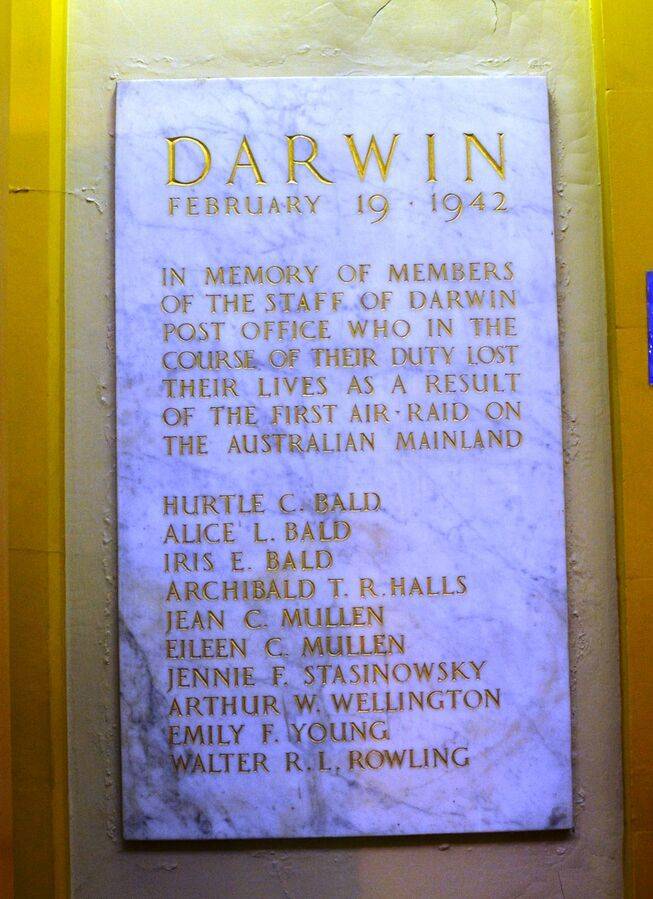

On 25th March, 1955, while Minster for Territories, Hasluck unveiled a plaque in memory of those who died at the Darwin post office during the first Japanese raid. In his speech he referred to the “panic evacuation” after the bombing and to 19th February as “the anniversary of a day of national shame”.

photograph: Georgina Bliss

Hasluck was not present in Darwin on 19th February, 1942 but Mr. F. W. Drysdale, MLC was. He has stated that he saw no evidence of panic that could not have been avoided if the military and civil authorities had done anything about performing their directive activities. Hasluck had many critics and the Darwin N. T. News editorial stated that “this was not an occasion for the political butchering of a piece of dead history.”

Another correspondent, Mr. J. A. McDonald wrote to the editor of the N. T. News accusing Hasluck of “eating our salt, drinking our beer and insulting his hosts by declaring that this was our day of shame. He agreed that there had been an exodus but it was lead “by departmental heads and their satellites”.

There are very few comprehensive first hand records of what happened on 19th February largely because of government censorship and that there were not many civilians left in the town. One of the few, and the one I consider the most, possibly only one, is that of Douglas Lockwood, a very highly regarded lead writer for the Melbourne Herald. He was there, and his book Australia Under Attack, published in 2005 is the most authoritative record of what happened. That includes the report of the Royal Commission which is a collection of evidence taken 6 weeks after the event from only those who remained and were available. Lockwood challenges some of the conclusions reached by the RC as patently wrong.

Women and children being evacuated from Darwin by ship on December 1, 1941

It is interesting to note that Lockwood wrote to Paul Hasluck, then Minister of Defence in 1964 seeking permission for access to the transcript of evidence taken on oath by the RC. Hasluck refused permission stating that many service witnesses had been assured of secrecy.

This is pertinent because the most direct and damning criticism of the RC was directed at the Air Force and the Army. The RAAF, in particular, came in for much criticism as its members were ordered by their CO to “take to the bush”, and they did. The Army, on the other hand, led by the Provost Corps, remained and was the leading element in the looting of abandoned houses. The few civilians who remained in town after the raid were forced to arm themselves to protect their homes and possessions from marauding soldiers, mainly military police, intent on helping themselves to whatever they could get their hands on.

The chief protagonist was Sergeant MacArthur Onslow of the Provost Corps. A known drunkard and bully, he marched into the civilian police station on the day after the raid brandishing a revolver and stated that Darwin was now under martial law and that the four civil policemen “.will now take orders from us.”

The civil police, who knew no better, believed him and under MacArthur Onslow’s instructions proceeded to order the remaining civilians to get out of Darwin. The looting started soon after. The military police split to town into sections and allocated them to specific groups who had exclusive access to whatever they could steal.

Excerpt from Chips Rafferty movie " The Overlander " Not only people were evacuated, but cattle as well.

Captain Bernard Coleman who controlled the Provost Corps told the RC that he was powerless to stop what was going on

The first orderly evacuation was organised by Chief ARP Warden Miller who scheduled 822 people on the basis of need to be taken south on the army supply ship Zealandia due to depart on 14th December. Administrator Abbott rescinded this plan and substituted an allocation based on addresses rather than need. When this was eventually sorted out the first group of evacuees left on 19th December, 1941 on board the Koolinda, a coastal cargo and passenger ship, followed by another 530 on the Zealandia the next day.

As fortune played out, an American liner, President Grant had escaped from Manila and took another 222 to Brisbane on 23rd December.

The MV Koolinda

Although the departures of these civilians was orderly the arrangements in getting them on board were chaotic thanks to the ineptitude of Administrator Abbott. He interfered with what the wardens were arranging and devoted most of his time arguing about who had authority to do what. At government House he employed four policemen to pack and load the government china and silverware which he sent on to Alice Springs by car with his wife. He determined that orders prepared by the ARP Warden and Permanent Civil Defence Officer had no authority because a national Emergency had not been declared. In brief, he did nothing positive himself but prevented others from taking charge and doing their duties.

At a public meeting on 7th January, 1942 a unanimous motion was passed that the Administrator be sacked. He was not but had he been there was no immediate replacement available. It was an established fact that the Administration did not have powers to order an evacuation, this could only occur if and when the federal government proclaimed a State of Emergency. In that respect Abbott was technically correct but nevertheless the Administration proceeded to delude the population into believing that it did have statutory power to order their removal and a steady orderly flow of volunteer evacuees ended with 1,900 women and children being evacuated in the period from mid-December to 1st February, 1942. A further 300 left in the following 18 days on returning aircraft ferrying wharf labourers from Queensland. The population at that stage was reduced to about 2,000.

Following the raids on 19th February, the last orderly evacuation took place when the Army laid on a train which would take them to Larrimah and then by road to Alice Springs. The train was laid on for women, children and elderly people. Younger men who tried to force their way on board were subdued when two soldiers, armed with sub-machine guns, were brought in to support the Chief Air Raid Warden. A second train was being organised for later the same night but this effort was abandoned when drunk, armed and out of control provosts prevented any men from boarding.

Darwin Post Office before the Bombing

The disorganised stampede began on December 11th when a soldier threw a brick through a shop window and set off an air raid alarm. Provosts and civilian police acting under the provosts orders began ordering people to evacuate by whatever means they could but were not allowed to use civilian cars. Following the air raid this reached a crescendo of vehicles of all and any kind heading for Adelaide River. There are several conflicting accounts of what happened but the RC concluded that the mass evacuation was no different to the behaviour of citizens in European countries faced with an invading force and that there was no panic. Douglas Lockwood disagrees with the RC on that point and its interpretation of the evidence.

However, what fault may lie at the feet of the civilians does not justify the remarks of Hasluck in 1955. Any accusation of national shame should be reserved for absconding soldiers and particularly the RAAF, the members of which fled in clear panic as soon as the second raid ended.

The RAAF personnel were mainly service personnel, not air crew or base defence staff. Without any logical basis they were ordered to “take to the bush”, about a mile away, where they were to re-assemble and be fed. Admittedly the RAAF base had been heavily bombed and the hospital was overloaded with injured airmen and evacuees from the Dutch East Indies. Thankfully the bedridden occupants had been moved into trenches dug in preparation for such an emergency and were saved.

Darwin Post Office after the bombing

The RAAF came in for most of the criticism of the Lowe RC, particularly the senior commanders for their failure to maintain good order and discipline. The senior RAAF officer at the time was Group Captain F.R.Scherger who later became Air Chief Marshall and the most senior of all RAAF officers. In light of the degree of panic and the seriousness of the chaos that prevailed, Scherger got off very lightly from the RC.

The principal target for blame from the RC was the base commander, Wing Commander Griffith, for his failure to maintain good order and discipline among his men, his failure of leadership and the desertion of his base by his men.

Even today in 2023, it is difficult to be adamant about pointing any finger of blame due to the conflicting evidence before the RC, some of which was contradictory evidence from the same witnesses, and as Lockwood has pointed out, the flawed interpretation of the evidence of Mr. Justice Lowe. Compounding these flaws is the ironclad secrecy imposed by the then federal government which is still in place today.

There are many tales of great bravery and sacrifice by individuals from all walks on the day of the raid but it is totally baseless to accuse the civilian population of acts of national shame. Such accusations should start with the first Menzies government and the retention of Abbott as Administrator with the powers that he was given and failed to use.

Next in line is the Provost Corps of the Army. Their behaviour was consistent with the reputation held by all who have served in the army that they are the dregs of the service. Major General Blake was the subject of criticism from the RC and the failings of his troops and the Provost Corps in particular.

Finally, The mass panic and chaos displayed by the base staff of the RAAF who should have set an example to the remaining civilians and the failure of their senior officers.

Part One

Part Two

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS