A moment comes, which comes but rarely in a nation’s history, when a new star is born in the political firmament.

In the years ahead, Australians might well look back on Thursday September 14, 2023, as one such moment.

That was the day on which Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, the Shadow Minister for Indigenous Australians, spoke from the heart and the head in a nationally televised address at National Press Club (NPC) in Canberra.

Before getting to the substance of her comments, five introductory remarks that set the tone for her prepared speech and the Q&A interaction with the audience.

Preamble

First, owing to renovations in the building it was explained that Price had to speak in a tiny apology for a room that was an embarrassment to the importance of the occasion. As Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth laments, that is a stain on the NPC that not “all great Neptune’s ocean” will wash clean. Price herself referred to that only obliquely at the very start of her talk by expressing appreciation for “the intimacy of the room,” which in itself is a clue to her sense of gentle irony.

Second, David Crowe, chief political reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age (Melbourne), who acted as MC, introduced her as a Warlpiri–Celtic woman. The relevance of this became clear in what followed. Third, he referred to Colin Lillie as her “partner.” Six seconds into her talk, Price corrected Crowe: “Colin is my husband, not my partner.”

She had me from that point on. With her two comments, Price grabbed and retained my full attention.

Fourth, in 2021, Price wrote a short policy paper for the Centre for Independent Studies called “Worlds Apart: Remote Indigenous disadvantage in the context of wider Australia.” She described the plight of Aboriginal-Australians living in remote communities as a “wicked problem” that is almost impossible to solve, with many “townships on the verge of breaking point.”

In a country known for its “wealth, education and safety,” they are “outliers” whose problems “are immensely challenging to understand, and their challenges [are] hard to address.” She issued a clarion call for a “solution that targets communities based on evidence, rather than assertions about race and culture, and focuses on establishing the safe communities that any Australian would rightfully expect on their doorstep.”

Thus Price has a demonstrated commitment to trying to understand and address the sorry state of affairs in remote Aboriginal communities. She brings the requisite dose of realism instead of starry -yed romanticism to her portfolio.

As of 19 September, it has been viewed by around 114,000 people. By way of comparison, the previous week’s address by a leading Yes campaigner Marcia Langton, who will feature again shortly, had been viewed 18,000 times despite being available for a full week longer.

It deserves a global audience, for the issues she discusses with exceptional eloquence, clarity, courage of conviction, and flashes of passion are relevant to public policy debates in every settler country (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, USA).

Fifth and finally, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is the Magna Carta of the international human rights regime. Article 1 declares: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Article 2 follows with: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, … birth or other status.” On any plain reading, the proposed Voice would violate this foundational global document.

An Alternative Moral Vision and Framework

Price used the platform of the NPC to lay out both a grounded critique of the Voice initiative and a compelling alternative vision. She devoted a lot of time to dismantling the flawed assumptions and false claims of the Yes campaign, all of which can be expected to be challenged. She has confronted the entire establishment and orthodoxy of Aboriginal political power and left them distinctly discombobulated.

Price has set down markers against everyone who would divide Australian society and embed separation in the Constitution. But she doesn’t just reject the Voice. Her political agenda is first to defeat the Voice in the referendum on 14 October and then to merge Aborigines into the wider Australian society.

Over the course of an hour, Price demonstrated astonishing range, depth, and grasp of on-the-ground issues. Her truth-telling – a perfect example of tough love – is not for the faint of heart and the squeamish. It is likely to bend the trajectory of the campaign and confirm her as a force of Australian and Aboriginal politics to be reckoned with. She is a national leader in the making with the potential to go to the very top of public life.

Of course, before Price can make it to the top, she will have to broaden her portfolio responsibilities beyond indigenous affairs. But she has shown she has the necessary qualities for an effective centre-right leader. Mercifully too, she is not a careerist pursuing power for the sake of power, but seems interested in public office to make a difference for the people.

Price quickly identified the inherent contradiction at the very core of the Voice idea which fatally undermines the “Closing the Gap” slogan. Given the difficulties of constitutional amendment, if the Voice is created, it will be forever. Therefore it is built on the assumption of a permanent gap and Aboriginal disadvantage. This will result, she followed up, because the city-based activists who have benefitted from the range of benefits, services, and programs dedicated to helping Aborigines are seeking to make their advantages permanent.

The price will be to turn Aboriginal-Australians into perpetual victims. By contrast, her own preferred pathway to progress is through a mix of institutional accountability of the existing machinery and programs, and individual agency and responsibility.

Instead of creating additional layers of Aboriginals-centric bureaucracy, she urged sharper focus on making the existing structures work to their benefit, conducting a full forensic audit of just where the annual $30-40 billion expenditure on Aboriginal programs is going and how effective it is, demanding accountability of institutions while encouraging individual and tribal agency and responsibility, and looking to the day when a separate Minister and Department can be abolished as public policy and benefits shift progressively from race to needs-based programs.

Price refutes the notion that “inner-city activists speak for all Aboriginals.” When she rejects the assumption underlying the Voice – that all Aborigines feel, think, and desire the same things as colonial-era stereotyping – she reminds me of an old Punch cartoon. A society lady introduces a guest from a West African country to another from India with the words: “You are both natives. You must have a lot in common.” Her vision will appeal to a much broader cross-section of Australians than just the Aborigines.

Price is a threat to the city-based power structures because she rejects the moral foundations on which the existing Aboriginal industry has been created. She is prepared to articulate an alternative moral framework as the pathway to genuine reconciliation and eventual union. This is why veteran Australian journalist Paul Kelly’s takeaway from the NPC address was: “Australia’s elites are in the process of being administered a huge shock.”

This includes the corporate elites. In his Sydney Morning Herald column on 15 September, David Crowe listed the elite money behind the No campaign. True enough, but not the whole truth. Financial support for No fades into insignificance in comparison to the serious money backing Yes. The final month of the campaign will be drenched with a $100 million “Vote Yes” advertising splurge.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese proudly boasted in Parliament:

“Every major business in Australia is supporting the Yes campaign. Woolworths, Coles, Telstra, BHP, Rio Tinto, the Business Council of Australia, the Catholic Church, the Imams Council, the Australian Football League, the National Rugby League, Rugby Australia and Netball Australia are all supporting the Yes campaign.”

Price noted that politicians could not be found in Canberra to listen to ordinary Aboriginal women who had travelled there to tell their lived truths. They listen instead to “the Qantas-sponsored leaders of the activist industry.”

The State of Victoria’s Yoorrook Justice Commission’s “truth-telling” relies on “make-believe history,” in the words of one of the country’s most eminent historians Geoffrey Blainey, to demand a separate child protection and criminal justice system for young people designed and controlled by Aboriginal-Australians. Price referenced the Commission in her NPC speech by decrying the tendency to romanticise pre-European Aboriginal culture. They misrepresent it as some form of paradise, she said, while demonising colonial settlement in its entirety and nurturing a national self-loathing about the foundations of the modern Australian achievement.

Melbourne University’s Professor Marcia Langton is another prominent Aboriginal Yes campaigner. On 11 September she explained the resistance to the amendment with reference to “base racism” and “sheer stupidity.” She has form. Speaking at a Queensland University event on 7 July, she said a large number of No voters and around 20 percent of the population were “spewing racism.”

Price responded to Langton at the NPC without naming her. What “would be racist, is segmenting our nation into ‘us’ and ‘them’.” And stupidity would lie in dividing

“a nation when it has been growing ever more cohesive. To split it along fractures of race rather than try to bring it closer together.”

Abuse

Price has copped a lot of vitriol and abuse from the establishment, and not just Aboriginal activists. On 8 April 2021, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC, the public broadcaster) issued a public apology to Price and settled out of court for its coverage of a speech by her in Coffs Harbour on 10 September 2019 “which it accepts were false and defamatory.”

Speaking on ABC Radio in November last year, senior Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson said with reference to Price that while the “bullets are fashioned” by conservative think tanks like the Centre for Independent Studies and the Institute of Public Affairs who pull the strings, “it’s a black hand pulling the trigger.” The CIS and IPA “strategy” is “to find a black fella to punch down on other black fellas.”

In an article in the Saturday Paper on 25 August 2018, Langton had similarly accused Jacinta Price and her Aboriginal mother Bess of having “become the useful coloured help in rescuing the racist image” of conservative think tanks.

It doesn’t require much imagination to know what would happen to any non-Aboriginal Australian who described Langton or Pearson in equivalent terms.

Those determined to take offence and see racism will find it every time. I became an Australian citizen in 1998. Not one to take intentional offence lying down, in the quarter-century since I have not encountered any serious racism as distinct from curiosity about origins. Not even during a two-week driving holiday through the outback.

Australia already is one of the most diverse, inclusive, and least racist societies in the world and there is a lot to like in this big picture. Of course there must be some racists here as anywhere else. But caste, skin colour, and religious prejudices are still far more deeply entrenched in India, for example, than here. And the fact that caste identity is constitutionally entrenched in India has served only to perpetuate caste consciousness and embed it deeply in public policy.

The Q&A Was Electrifying

In the Q&A, Crowe asked if Price accepted that the history of colonisation has caused “generations of trauma.” Her answer provoked much applause and laughter:

“Well, I guess that would mean that those of us whose ancestors were dispossessed of their own country and brought here in chains as convicts were also suffering from intergenerational trauma. So I should be doubly suffering from intergenerational trauma.”

The division that will be entrenched permanently by the constitutional amendment is very personal in a “blended” family. The cut-away from her doubly traumatised answer focussed on the centre of the first row of the audience where her Aboriginal mother Bess sat in the centre, amidst her father David who is an Australian of Anglo–Celtic ancestry and her husband Colin who is Scottish-Australian. Price has three sons from her first marriage and is stepmother to Colin’s son from a previous relationship. This means, as they have noted, that, if approved, the Voice would give additional ancestry-based rights, privileges, and access to her mother and three sons but not to her father, husband, and stepson. That sounds like a recipe for Tolstoy’s unhappy families.

Price continued in answer to Crowe that violence inside the family resulted more from child marriage of girls than from the lingering effects of colonisation. Then she added:

We haven’t had a feminist movement for Aboriginal women because we’ve been expected to toe the line in Aboriginal activism for the rights of our race. But our rights as women have been second place.

In another blunt response to a question on the growing number of Australians who identify as indigenous, she said: “If we chose to serve Australians on the basis of needs and not race, those opportunists” who self-identify as Aboriginal “would disappear quick smart.”

To a follow-up question on the continuing impact of colonisation, from Josh Butler of the Guardian, Price said she doesn’t believe there are ongoing negative impacts but she does think there is ongoing positive impact. Taken literally, this is of course easily demonstrated as false. (Although ongoing trauma from historical colonisation is more likely to be the product of a contemporary sensibility that puts a premium on victimhood and grievance.) In all cases, colonisation had both damaging and beneficial lasting impacts in the various empires.

Maybe Price meant that the balance of the impacts of colonisation has been positive. That at least is defensible and arguable. The exercise would require rigorous historical assessment of the net benefit-cost analysis. In Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (William Collins, 2023), Nigel Biggar has stirred controversy by highlighting the many beneficial as well as baleful legacies of the British Empire.

Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney found Price’s comments “offensive” and “a betrayal.” Yet Burney is a cabinet minister in a Westminster-style parliamentary government. Surely that counts as a positive continuing impact of colonisation? There are altogether 11 Aboriginal-Australian members of Australia’s parliament. Their status, Price noted, cannot but be diminished if the Voice is created as a de facto third chamber.

Albanese Misread the Nation

The emergence of Price as a powerful Aboriginal-Australian voice and an effective campaigner has both overshadowed and, so far at least, is sinking the Yes case. She has woven deeply personal stories of family dysfunction, alcoholism, domestic violence, sexual abuse of children, and murders as the everyday reality of people living in remote communities while the academic activists in the main cities obsess over colonial atrocities and a constitutional Voice.

In a previous article in the Weekend Australian, I had argued that Burney was prudent in refusing to agree to a public debate with Price because of the latter’s obvious superiority in intellectual firepower and cut-through messaging skills. (Burney does, however, have a good eye for designer glasses and clothing with Aboriginal motifs.)

After her NPC address, I believe Price would leave even Albanese in the dust in any public debate between the two. For Albanese seems to lack both the capacity and the inclination to master his brief on this signature initiative. Having repeatedly promised to implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full, the text of which runs to 26 pages, he insists it is only one page long. In an act of prime ministerial delinquency, he made the jaw-dropping confession that he had only read the cover page summary and asked “Why would I” read the rest?

Albanese accepted the activists’ maximalist demands in framing the referendum wording that requires a one Yes or No answer to two distinct questions: on recognition, and on a new body to be called the Voice. He rebuffed the opposition leader’s efforts to negotiate a bipartisan question. He rejected advice from Bill Shorten, a cabinet minister and former party leader, to first legislate a Voice body, enact recognition of Aboriginal Australians in the Constitution’s Preamble, let people become familiar with the workings of the Voice and, if it proves successful and people’s comfort level with it increases, only then consider a constitutional amendment at that stage.

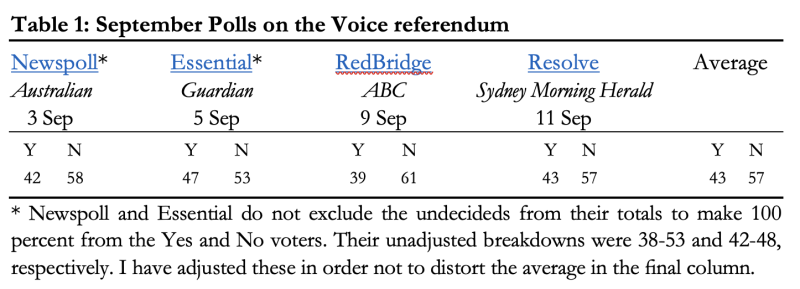

Meanwhile, support for the Voice continues a downward slide in all public opinion polls. The rising support for No is emboldening more politicians and prominent Australians to come off the fence and also encouraging more citizens to speak up.

The Redbridge poll also asked voters to rank their reasons for opposing the Voice. In order, the top three reasons were its divisiveness, lack of details, and it won’t help Aboriginal-Australians.

As someone whose self-confessed animating passion in public life is the love of “fighting Tories,” perhaps Albanese misjudged the initial overwhelming but soft support for the Voice as a good issue on which to wedge the opposition coalition. Ironically, therefore, should the referendum fail as looks likely on present polls and their trajectory, Price will emerge with strengthened authority and enhanced credibility while Albanese will be a much diminished PM.